The Death of Corporal Robert Owen

Robert Owen was 30 years old when he left his job as a local ironworker and joined the Erie Bureau of Police on June 14, 1971. An Erie native and a U.S. Navy veteran, Owen was persuaded to join the police by two young officers who had befriended him.

"When (Police Chief Charles Bowers) and I were rookie patrolmen we used to stop by Bob's house and have coffee. At different times Bob would ride in the cruiser with us," said Dennis Tobin, former deputy chief. Tobin, who first met Owen in 1963, described him as a big, tough guy who knew the streets of Erie well. Owen never took a back seat to anybody, Tobin said, and brought his assertive, no-nonsense style with him to the job. "He enforced the law the way it was supposed to be enforced," Tobin said. "If he knew he was in the right and you were wrong, he would enforce the law. Some people could consider that hard. I consider that good police work."

Owen became a motorcycle patrolman in the bureau's Traffic Division in 1972. He was promoted to corporal and unit supervisor six years later. Three years later Corporal Robert Owen was a nine year veteran of the Erie Police department when he was found dead at about 1:40 a.m. on Monday morning, December 29, 1980. Investigators believe that he was shot shortly before midnight on Sunday. His body was lying about 75 feet away from his patrol car — Car 113 — with a single bullet wound to the chest. The murder weapon was his own — a Colt Trooper Mark III .357 with a 6-inch barrel, bearing serial number 235575L.

Owen’s patrol car, which was parked in a secluded industrial area known where Erie police officers often gathered, was idling. It’s lights were off and the driver’s door was open. In addition to being known as a police nest for patrol officers, the area was also known for drug addicts looking to steal chemical solvents, like toluene, often stored outside the warehouses located off of West 18th Street. The police radio inside Owen’s vehicle was turned to channel three, which was a car-to-car channel used by officers to privately talk to each other.

About 70-75 feet away from the patrol car was the lifeless body of Corporal Robert Owen. The condition of Owen’s jacket and shirt indicated that he was likely involved in a struggle before he was shot. His keys, a set of handcuffs with one cuff partially open, were found near the start of a bloody trail north of the patrol car and several feet away from the body, suggesting perhaps that Owen might have either attempted to reach his car or was partially dragged in that direction. Also present were cigarette butts from two different brands of cigarettes and a lighter — Owen’s weapon was not immediately found.

According to investigators, a man walking his two dogs saw Owen’s unattended patrol car and a flashlight, and notified Erie Police about 1:40 a.m., Monday morning. What that man, identified as David Cambra, reportedly did not initially mention is that he also found and pick up Owen’s gun, and kept it. When questioned on January 09, 1981, Cambra reportedly admitted to picking up the weapon then later disposing of it about a mile from the scene near the railroad tracks west of Pittsburgh Avenue, near West 15th Street and Greengarden Boulevard — ostensibly when he learned it was used to kill a police officer.

He ultimately led police detectives to the spot where he claims to have tossed the weapon, which laid exposed to harsh winter elements for over 11 days. The weapon was found to have traces of Owen’s blood in and on the barrel, indicating the gun was fired at close range. David Cambra reportedly underwent polygraph examinations about his possible involvement in the murder of Robert Owen. He allegedly passed those examinations.

Many problems were encountered with the investigation. The crime scene was destroyed by the many police officers, paramedics, and others who rushed to it after the initial reports of Owen's shooting came in. Footprints and tire tracks were ruined of any chance of being preserved as evidence by a decision to have firefighters hose down the area to wash away the blood stains that littered the snow. It was the first time in 30 years that an Erie policeman had been murdered on the job and everyone wanted to take charge of the crime scene, but no one preserved the crime scene. One potentially valuable piece of evidence police thought they had was a lighter found at the scene. The lighter was bagged as evidence, but disappeared on its way from the crime scene to the Erie police station.

At about midnight on the night of Owen’s death, two truck drivers reportedly saw the silhouettes of three (3) people, including one who appeared to be a police officer, standing near the warehouse where the body of Owen was found. They also reported seeing the idling police cruiser nearby.

The murder of Corporal Owen has been the subject of much speculation over the years. Although ruled a homicide by coroner Merle Wood, some investigators believed Owen committed suicide. The death of Robert Owen was officially ruled a homicide by Pennsylvania’s Attorney General, LeRoy Zimmerman, on April 14, 1983.

Small organized groups, whose members later claimed they had the help of police, had been looting homes of jewelry, cash and other valuables. Also, Gambling, including numbers running and sessions of a high-stakes illegal dice games called barbotte, was rampant, which lead to the controversy that surrounded Robert Owen’s role in the investigation of a high-value burglary that took place on or about November 25, 1980 at the home of Louis Nardo, who resided at 605 Hilltop Road in Erie. According to criminal records, the burglary resulted in the loss of jewelry and other valuable items from the Nardo home estimated $550,000 in value.

Owen and other police officers responded to the burglary and were at the premises when a diamond ring that was not taken in the burglary turned up missing. Owen and eight other officers were questioned about the theft. Owen and two other police officers were administered polygraph tests. According to initial reports, the test results of the two other officers were inconclusive, while it was reported that Owen’s polygraph results were off the charts. The other two officers were retested and reportedly passed, while Owen never had the opportunity to take the test that was scheduled on the day he was found dead. The issue regarding the missing ring has since been solved.

At that time, an active burglary ring associated with Erie crime figure, Caesar Montevecchio and Samuel Fat Sam Esper, was active. Esper would later be a cooperative witness with police and agreed to wear a wire during a conversation with Montevecchio about the murder of Robert Owen. The conversation reportedly fell flat, with Esper saying to Montevecchio “I wonder who killed Owen?” Montevecchio reportedly replied “you know who killed Owen” and ended the conversation.

According to investigative reports, Owen, a traffic investigator with a no-nonsense reputation who ran an auto wrecking business on the side, was on duty while at a card game at a close friend’s house, off of West 16th Street, near the location where his body was found. While there, Owen called his wife, then called a fellow police officer before placing a telephone call to an unknown party at about 11:45 Sunday night, but investigators were unable to determine who Owen called.

In March 1991, the investigative murder file of Robert Owen was found in a file cabinet inside the City of Erie Solicitors office. According to reports at the time, City Solicitor, Paul Susko, found the file and was stunned by the contents, which included confidential police reports and reports from the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office.

The case has never closed. It was passed on to other Erie police detectives, state police investigators and the State Attorney General's office. All developed thick case files, but none found that key piece of information or evidence to solve it. The Attorney General's office gave the case back to local investigators in December 2000 and Erie County District Attorney Brad Foulk turned it over to state police investigator Trooper Dana Anderson and Erie Deputy Police Chief James Skindell.

"When (Police Chief Charles Bowers) and I were rookie patrolmen we used to stop by Bob's house and have coffee. At different times Bob would ride in the cruiser with us," said Dennis Tobin, former deputy chief. Tobin, who first met Owen in 1963, described him as a big, tough guy who knew the streets of Erie well. Owen never took a back seat to anybody, Tobin said, and brought his assertive, no-nonsense style with him to the job. "He enforced the law the way it was supposed to be enforced," Tobin said. "If he knew he was in the right and you were wrong, he would enforce the law. Some people could consider that hard. I consider that good police work."

Owen became a motorcycle patrolman in the bureau's Traffic Division in 1972. He was promoted to corporal and unit supervisor six years later. Three years later Corporal Robert Owen was a nine year veteran of the Erie Police department when he was found dead at about 1:40 a.m. on Monday morning, December 29, 1980. Investigators believe that he was shot shortly before midnight on Sunday. His body was lying about 75 feet away from his patrol car — Car 113 — with a single bullet wound to the chest. The murder weapon was his own — a Colt Trooper Mark III .357 with a 6-inch barrel, bearing serial number 235575L.

Owen’s patrol car, which was parked in a secluded industrial area known where Erie police officers often gathered, was idling. It’s lights were off and the driver’s door was open. In addition to being known as a police nest for patrol officers, the area was also known for drug addicts looking to steal chemical solvents, like toluene, often stored outside the warehouses located off of West 18th Street. The police radio inside Owen’s vehicle was turned to channel three, which was a car-to-car channel used by officers to privately talk to each other.

About 70-75 feet away from the patrol car was the lifeless body of Corporal Robert Owen. The condition of Owen’s jacket and shirt indicated that he was likely involved in a struggle before he was shot. His keys, a set of handcuffs with one cuff partially open, were found near the start of a bloody trail north of the patrol car and several feet away from the body, suggesting perhaps that Owen might have either attempted to reach his car or was partially dragged in that direction. Also present were cigarette butts from two different brands of cigarettes and a lighter — Owen’s weapon was not immediately found.

According to investigators, a man walking his two dogs saw Owen’s unattended patrol car and a flashlight, and notified Erie Police about 1:40 a.m., Monday morning. What that man, identified as David Cambra, reportedly did not initially mention is that he also found and pick up Owen’s gun, and kept it. When questioned on January 09, 1981, Cambra reportedly admitted to picking up the weapon then later disposing of it about a mile from the scene near the railroad tracks west of Pittsburgh Avenue, near West 15th Street and Greengarden Boulevard — ostensibly when he learned it was used to kill a police officer.

He ultimately led police detectives to the spot where he claims to have tossed the weapon, which laid exposed to harsh winter elements for over 11 days. The weapon was found to have traces of Owen’s blood in and on the barrel, indicating the gun was fired at close range. David Cambra reportedly underwent polygraph examinations about his possible involvement in the murder of Robert Owen. He allegedly passed those examinations.

Many problems were encountered with the investigation. The crime scene was destroyed by the many police officers, paramedics, and others who rushed to it after the initial reports of Owen's shooting came in. Footprints and tire tracks were ruined of any chance of being preserved as evidence by a decision to have firefighters hose down the area to wash away the blood stains that littered the snow. It was the first time in 30 years that an Erie policeman had been murdered on the job and everyone wanted to take charge of the crime scene, but no one preserved the crime scene. One potentially valuable piece of evidence police thought they had was a lighter found at the scene. The lighter was bagged as evidence, but disappeared on its way from the crime scene to the Erie police station.

At about midnight on the night of Owen’s death, two truck drivers reportedly saw the silhouettes of three (3) people, including one who appeared to be a police officer, standing near the warehouse where the body of Owen was found. They also reported seeing the idling police cruiser nearby.

The murder of Corporal Owen has been the subject of much speculation over the years. Although ruled a homicide by coroner Merle Wood, some investigators believed Owen committed suicide. The death of Robert Owen was officially ruled a homicide by Pennsylvania’s Attorney General, LeRoy Zimmerman, on April 14, 1983.

Small organized groups, whose members later claimed they had the help of police, had been looting homes of jewelry, cash and other valuables. Also, Gambling, including numbers running and sessions of a high-stakes illegal dice games called barbotte, was rampant, which lead to the controversy that surrounded Robert Owen’s role in the investigation of a high-value burglary that took place on or about November 25, 1980 at the home of Louis Nardo, who resided at 605 Hilltop Road in Erie. According to criminal records, the burglary resulted in the loss of jewelry and other valuable items from the Nardo home estimated $550,000 in value.

Owen and other police officers responded to the burglary and were at the premises when a diamond ring that was not taken in the burglary turned up missing. Owen and eight other officers were questioned about the theft. Owen and two other police officers were administered polygraph tests. According to initial reports, the test results of the two other officers were inconclusive, while it was reported that Owen’s polygraph results were off the charts. The other two officers were retested and reportedly passed, while Owen never had the opportunity to take the test that was scheduled on the day he was found dead. The issue regarding the missing ring has since been solved.

At that time, an active burglary ring associated with Erie crime figure, Caesar Montevecchio and Samuel Fat Sam Esper, was active. Esper would later be a cooperative witness with police and agreed to wear a wire during a conversation with Montevecchio about the murder of Robert Owen. The conversation reportedly fell flat, with Esper saying to Montevecchio “I wonder who killed Owen?” Montevecchio reportedly replied “you know who killed Owen” and ended the conversation.

According to investigative reports, Owen, a traffic investigator with a no-nonsense reputation who ran an auto wrecking business on the side, was on duty while at a card game at a close friend’s house, off of West 16th Street, near the location where his body was found. While there, Owen called his wife, then called a fellow police officer before placing a telephone call to an unknown party at about 11:45 Sunday night, but investigators were unable to determine who Owen called.

In March 1991, the investigative murder file of Robert Owen was found in a file cabinet inside the City of Erie Solicitors office. According to reports at the time, City Solicitor, Paul Susko, found the file and was stunned by the contents, which included confidential police reports and reports from the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office.

The case has never closed. It was passed on to other Erie police detectives, state police investigators and the State Attorney General's office. All developed thick case files, but none found that key piece of information or evidence to solve it. The Attorney General's office gave the case back to local investigators in December 2000 and Erie County District Attorney Brad Foulk turned it over to state police investigator Trooper Dana Anderson and Erie Deputy Police Chief James Skindell.

|

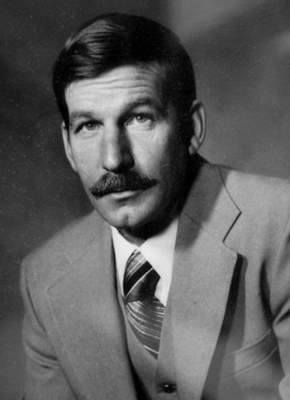

| Corporal Robert Owen. |